Mark Montgomery, Grinnell College – International Adoption

Fewer and fewer children are being adopted from overseas.

Fewer and fewer children are being adopted from overseas.

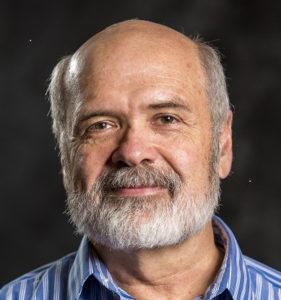

Mark Montgomery, professor of enterprise and leadership at Grinnell College, determines the reasons why international adoption rates are falling.

Mark Montgomery is Donald L. Wilson Professor of Enterprise and Leadership, and Professor of Economics, at Grinnell College. He is coauthor, with his wife and colleague Irene Powell, of Saving International Adoption (Vanderbilt University Press, January 2018.) Mark teaches Mathematical Economics, Econometrics, the Economics of Education, and Environmental Economics. His research has appeared in numerous academic journals including The Review of Economics and Statistics, Economic Inquiry, The Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control among others; his essays have been published by The Chronicle of Higher Education, Inside Higher Education, The Times Higher Education, The Conversation and other places. His commentary has been heard on Public Radio International’s To the Best of Our Knowledge. He is coauthor, with Irene Powell, of a mystery novel, Theoretically Dead (New Victoria Publishers, 2001). He received his Ph.D. from the University of Wisconsin – Madison in 1982. He and Irene Powell have three grown children, two of them adopted.

International Adoption

International adoption is in a state of near collapse. In 2005, almost 46,000 children were adopted across borders; by 2015 the number had dropped by 72%. Why has this happened? One key factor is national pride. South Korea had been sending children to the U.S. since the early 1950s; 6,000 came in 1987 alone. But when, during the 1988 Seoul Olympic games, the country got criticized for “exporting” its offspring, the numbers started falling sharply. In 2016 fewer than 300 Koreans were adopted by Americans. In 2012 Russia ceased all adoptions to the U.S. when Congress sanctioned some Russian officials after an anti-corruption activist died suspiciously in a Moscow jail. Vladimir Putin said, “The country will not be humiliated”.

Anti-adoption pressure also builds when the western press reports so-called “child trafficking” scandals. In a few cases these scandals involve birth parents being defrauded of their children, not knowing they would be placed permanently outside the country. More commonly, however, children are said to be trafficked because some impoverished mothers are found to have been compensated for placing a child for adoption.

Of course, not everyone laments the decline of international adoption. Some critics say it exploits poor families and is too influenced by commercial interests. UNICEF wants to supplant the practice with local solutions like domestic adoption or family reunification. Our research suggests, however, that these alternatives have been ineffective at getting many children into stable, permanent homes.

Of course no country will say it’s closing adoption due to pride and publicity, they will say that shutting it down is in “the best interest of the children.” Given how many kids are growing up without permanent families that argument is not espectially convincing.