Kishwar Rizvi, Yale University – Iran and Global Exchange in the Early Modern Period

What if art was seen as a more important part of our culture?

What if art was seen as a more important part of our culture?

Kishwar Rizvi, associate professor in the history of art at Yale University, delves into when art was seen as an important commodity among kings and queens.

Kishwar Rizvi is Associate Professor of Islamic Art and Architecture at Yale University. She is currently writing a book on cultural production during the reign of Shah Abbas and global early modernity. Among the achievements in the Shah were the establishment of a cosmopolitan new capital city, Isfahan, and global exchange centered on Safavid Iran. Elites patronized new architecture and commissioned beautiful works of literature and painting. Together, these productions serve as representation of Shah Abbas and provide insights into his role in world history.

Professor Rizvi has written on representations of religious and imperial authority in Safavid Iran, as well as on issues of gender, nationalism and religious identity in the modern Middle East and South Asia. She is the author of The Transnational Mosque: Architecture and Historical Memory in the Contemporary Middle East (University of North Carolina Press, 2015), which won the 2017 Charle Rufus Morey Distinguished Book Award from the College Art Association. Her earlier publications include The Safavid Dynastic Shrine: History, religion and architecture in early modern Iran (I. B. Tauris, 2011) and the anthology, Modernism and the Middle East: Architecture and politics in the twentieth century (University of Washington Press, 2008).

Iran and Global Exchange in the Early Modern Period

The mobility of individuals and ideas defines the early modern period, and was manifested in thriving cosmopolitan cities, from Isfahan to Venice, as well as trade that brought silks and ceramics to European households and illustrated print culture to the Middle East and South Asia. Art and culture were valuable commodities, playing a central role in diplomacy as well as in marking imperial authority.

Fig. 1 Vase. 17th century, Iran. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1966. Accession no. 66.107.1

The late sixteenth century is full of the names and exploits of great kings, from Shah Abbas in Iran to Elizabeth I in England and Ireland, and the Wan Li Emperor in China. These kings (and queen) vied for control over global trade networks, with the goal of expanding their commercial and colonial ambitions.

Safavid Iran was at the forefront of global trade, its connections expanding from Isfahan via land routes to Europe, as well as maritime ones in the Indian Ocean that brought wares from South East Asia to Yemen and onwards to Africa. Spices, scents, and decorative objects, like porcelains and carpets, were distributed over land and sea.

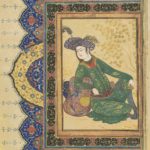

“A Prince Reclining against a Bolster.” School of Riza ‘Abbasi, Iranian, ca. 1565–1635. C. 1650. Yale University Art Gallery. Gift of Mary Burns Foss. Accession no. 1983.94.16

Beyond their commercial value, works of art served a diplomatic purpose as well. In 1603, Shah Abbas sent his ambassador to Venice with sumptuous gifts for the Doge, Marino Grimani. A massive painting by Gabriele Caliari in the Doge’s Palace shows the moment when Gimani was presented with precious gifts from the Safavid king, prominent among them a silk tapestry that inspired awe among the beholders. In return, the Doge sent back glassware, masks and silver mirrors. Iran was viewed as a central node in global exchange, one whose luxury goods were second to none.

During the early modern period, works of art were among the most valuable emissaries between different political and religious realms.

Silk Textile Fragment signed by ‘Abdullah. First half of the 17th century, Iran. Yale University Art Gallery. Hobart and Edward Small Moore Memorial Collection, Gift of Mrs. William H. Moore. Accession no. 1951.51.86

They serve as a lesson for us today; cultural and economic engagement with Iran may achieve exactly what isolationism has not.