Thomas Olsen, SUNY New Paltz – Shakespeare and the Art of the Remix

Was Shakespeare a plagiarist?

Was Shakespeare a plagiarist?

Thomas Olsen, associate professor and chair of the English department at SUNY New Paltz, discusses how the fabled author remixed other’s work to create his masterpieces.

Thomas G. Olsen joined the faculty at SUNY New Paltz in 1997. He teaches undergraduate and graduate courses in Shakespeare and in English literature, especially of the early modern period. He has a particular interest in Shakespeare’s adaptations of source stories, as well as in the other side of of that process: the ways that later writers and other artists have adapted and re-worked Shakespeare.

Shakespeare and the Art of the Remix

Tomorrow is St. George’s Day.

St. George is the patron saint of the English nation, famous for killing dragons and rescuing maidens.

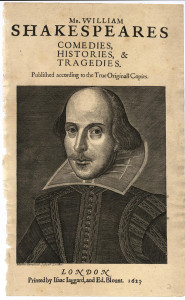

But April 23 is also the death day, and, coincidentally, possibly also the birth day of England’s patron saint of literature, William Shakespeare. In fact, tomorrow is the 400th anniversary.

What better tim e to remember Shakespeare’s achievements and to consider the nature of his creativity?

e to remember Shakespeare’s achievements and to consider the nature of his creativity?

In my years of studying, teaching, and writing about Shakespeare I have become more and more interested in how he ransacked the literature of his age, stealing storylines and characters from other authors, and remaking their works. Neither Hamlet nor King Lear, Brutus nor Caesar, Romeo nor Juliet were his original creations. He took their stories and almost all his stories from previously published or already performed works. He was a Renaissance “remix artist”—perhaps the greatest ever. As George Bernard Shaw once quipped, Shakespeare had a tremendous “gift of telling a story (provided some one else told it to him first).”

But does a talent for remixing make him a plagiarist? Thankfully not: the work of literary scholars and cultural historians reveals that his age had nothing like our notion of intellectual property or even authorship. It was a culture of copying: literary artists achieved greatness not through originality, but by adding nuances and dimensions to already familiar stories. It was a culture that valued the twice- or thrice-told tale—and this is the great paradox of his genius— so long as it was creatively redone. And creatively done his amazing body of works certainly is.

Thanks, Will, for all those great remixes!

Yes, I have written about this very thing. Probably things began to change with the Statute of Anne (1709/10) reserving for printers the right of copy, and later with the various acts of copyright, including the US Copyright Act of 1790. Notably, every time the copyright act was revised, the protections for the copyright owner increased. This is no doubt due to the Romantic obsession with the individuation of works, how the genius inherent in the poet or writer must not be bowdlerized by others. An important point is that it was almost impossible to make a living by writing alone in Shakespeare’s time. Later on, post-Samuel Johnson, a number of people subsisted chiefly by writing. The massification of literature was upon us, and it mattered more and more to publishers and writers that derivative authors should not unduly profit by stealing material from their forbears, although of course it still happened. This is why plagiarism and copyright violation is regarded as such a sin today; our current understanding of creativity does not admit of our debt to other authors. However, as literature, plots and scenarios have burst forth in such great number for centuries, and as the internet dutifully archives most of this, it will become apparent to the scholars of the future how very derivative the literature of today is. Just not overtly so, unlike as in Shakespeare’s day.