A. Park Williams, Columbia University – Megadroughts

Droughts have been in the news a great deal of late.

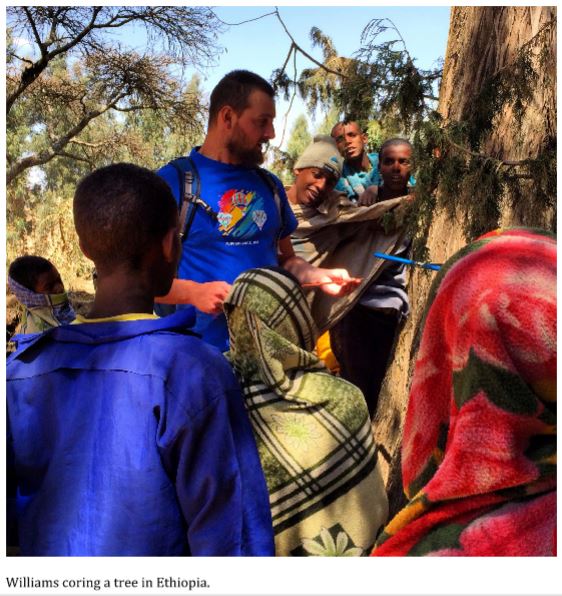

A. Park Williams, assistant research professor at Columbia University, is studying trees and learning a great deal about droughts in the process.

Park Williams is an assistant research professor at Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory. A bioclimatologist, his research straddles climatology and ecology. His specific interests focus on climate variability and change, and how these impact the living world. He wants to improve understanding of drought and its effects on ecosystems, carbon budgets, agriculture and humanity. His ultimate goal is to advance scientific knowledge in ways relevant and interesting to the public and policy makers.

Megadroughts

In the arid forests of the southwestern United States, trees grow rapidly during wet years, producing wide rings, and slowly during drought ones, producing skinny ones.

I study the year-by-year records left by these rings, and they tell a fascinating story more than a thousand years long, about life in a water-limited world. One of the most interesting chapters is a five-hundred year stretch ending in 1300 AD, when the Southwest was ravaged by a series of prolonged droughts. Climate scientists call them “megadroughts.”

Each megadrought lasted longer than a decade, and probably contributed to the abandonment of ancient cliff-dwelling cities such as Mesa Verde, in Colorado.

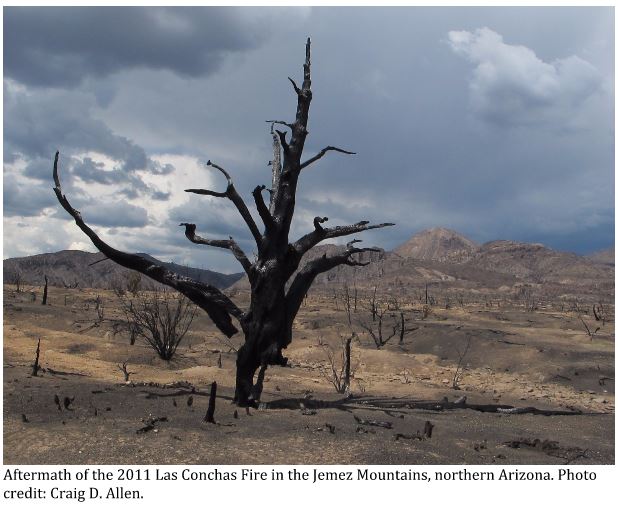

Currently, the Southwest is entrenched in a 15-year drought. Tree rings and climate data suggest that this ongoing drought is on par with some of the worst megadroughts of the past millennium. It’s been tough on forests, with nearly 20% ravaged by bark-beetle outbreaks and wildfires.

My research shows that warming greatly intensifies the impacts of drought on forests. So the knowledge that man-made global warming is only just beginning, combined with the knowledge that severe droughts can happen even without human influence, paints a grim picture for Southwestern forests.

Unlike trees, humans use ingenuity to survive drought. But our solutions may only serve as Band-Aids that hold together a deepening and widening wound. Modern water storage facilities and pumping of groundwater from deep wells have so far prevented us from meeting the same fate as the cliff dwellers. But these new sources of water may not last forever. We’re now seeing dried-up wells in some towns, and disturbingly low lake levels throughout the region.

Trees have been candidly recording what happens to living systems when water supply can’t meet demand. We would be wise to pay attention.

America is suffering the divine justice of God.