On University of the South Week: Platinum isn’t just for well selling music artists.

On University of the South Week: Platinum isn’t just for well selling music artists.

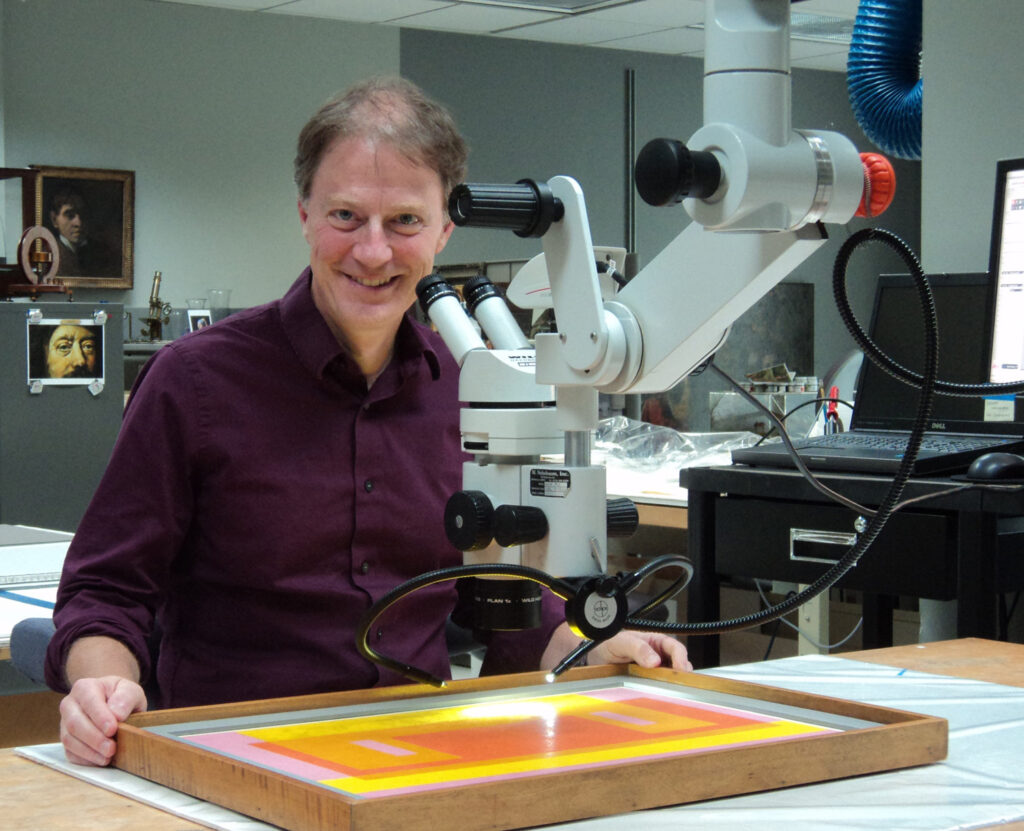

Rob Bachman, professor of chemistry, explores a benefit of this precious metal.

Rob Bachman earned a B.A. and a Ph.D. in chemistry at Rice University with a focus in inorganic, organometallic, and organic chemistry. He teaches a variety of upper level courses in inorganic chemistry, including inorganic chemistry, bioinorganic chemistry, structural methods, materials chemistry, and advanced environmental geochemistry. Bachman also co-directs the Office of Undergraduate Research and Scholarship. Last year, 379 Sewanee students (of 1,700 total students) were involved in mentored research or scholarship, and the university funded 54 summer research fellowships.

Designing New Platinum-Based Anti-Cancer Drugs

People generally don’t think about platinum playing a role in stopping cancer, but it does, courtesy of an unexpected discovery in the 1960s. Barnett Rosenberg was exploring whether electrical fields might play a role in cell division. Luckily for us, he chose platinum electrodes for these experiments, a choice that led to an astonishing discovery. The electrodes were generating small amounts of platinum-centered molecules that cause unusual cell division; suggesting that they might stop cancer in its tracks. After 15 years of research by many teams of scientists, one of these molecules made it to clinical use, a drug called cisplatin. Cisplatin is successfully used for many types of cancer but often has devastating side-effects.

Since then, my group, and many others, have designed new platinum-centered molecules that aim to keep cisplatin’s cancer-killing behavior while removing its side effects. In my mind, synthetic chemistry is naturally intertwined with art, especially sculpture. The novel molecules we design and create must have the correct shape to interact with the natural world as desired.

Listening to ours at a conference inspired me to sketched several new drug designs. My approach was a bit like Lego building without directions, interchanging available building blocks to achieve a goal. Numerous undergraduates working with me in my teaching and research laboratories have crafted many new molecules in the hope of creating better anti-cancer drugs. So far, our work has generated interesting new sculptures with unique chemical reactivity, and biological behavior similar to a critical step of cisplatin’s cancer-killing action. We know there are still many steps along the road to the ultimate goal, and that countless potential medicines often don’t work well enough for clinical use. Thus, the overarching goals of this work are simultaneously improving human health and growing the next generation of scientists.