When you think “big-data,” you may not immediately think of the genetic contents of the deep sea.

But, Holly Bik, a post-doctoral researcher at the UC Davis Genome Center, does!

Her research analyzes sea-water in an effort to “barcode the sea.”

Dr. Holly Bik obtained her Ph.D. in the United Kingdom, working at the Natural History Museum, London in conjunction with the National Oceanography Center, Southampton. She subsequently completed postdoctoral appointments at the University of New Hampshire and University of California, Davis, before accepting a position as a Birmingham Fellow in the group at the University of Birmingham, UK. Her research uses DNA sequencing and computational biology tools to explore the biodiversity of microbial species in diverse habitats, with an emphasis on marine and deep-sea ecosystems. She also contributes to Deep Sea News, a marine biology blog.

Holly Bik – The Diversity of Microbial Life

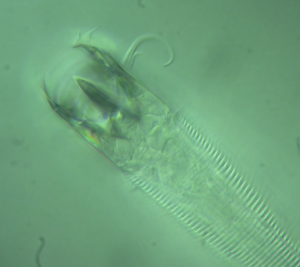

For anyone who’s watched the new “Cosmos” series with Neil De Grasse Tyson, you may have heard of the Tardigrade: it’s a microscopic animal that resembles a lumbering bear. Tardigrades are so tough that they can survive radiation in space as well as years of dehydration.

For anyone who’s watched the new “Cosmos” series with Neil De Grasse Tyson, you may have heard of the Tardigrade: it’s a microscopic animal that resembles a lumbering bear. Tardigrades are so tough that they can survive radiation in space as well as years of dehydration.

There are thousands of animal groups that exist practically everywhere, invisible to the naked eye. Diverse communities are always under your feet, burrowed in beach sand and nestled amongst the soil of a verdant lawn. These tiny species belong to an array of underappreciated Phyla: Gastrotrichs, Priapulids, Kinorhynchs, Platyhelminthes, and nematode worms.

Humans have been exploring the hidden animal world for hundreds of years, using microscopes to create taxonomic keys and illustrated natural history guides. This work is laborious and time consuming, and centuries later, we still haven’t made much progress. Global biodiversity is immense.

Recently, scientists have begun using environmental DNA sequencing to increase the speed at which we can characterize the diversity and geographic distributions of microbial communities.

My work focuses on marine sediments: we put mud into a blender, to liquefy cells and extract DNA, and then sequence a so-called “barcoding” gene to fingerprint the species that are present. One recent project used these techniques to study the impacts of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico.

Another focus of my work has been the development of data visualization tools. Environmental sequencing projects routinely grapple with hundreds of millions of DNA sequences, and analyzing data at this scale represents a significant research challenge.

It’s an exciting time in biology – we’ve truly entered the era of “big data”, and new DNA sequencing technologies are giving us an unprecedented view of microscopic communities.