As it continues to be an issue worldwide, a great deal has been written about infant mortality.

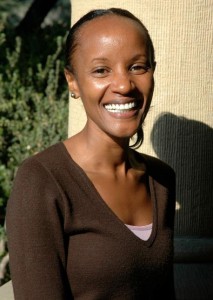

Lucy Thairu, an assistant consulting professor at the Stanford University School of Medicine, details this ongoing problem as it occurs on a small African island.

Dr. Thairu obtained a Masters’ degree in Biochemistry in France then an MSc. and a PhD in Nutrition from Cornell University. Her research at Cornell University was based on field studies in various countries in sub-Saharan Africa. The research emphasized the relevance of the social and economic context for the prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV/AIDS. The results were recognized with the Abraham Horwitz award from the United Nations’ Committee on Nutrition. From 2006 to 2009, Dr. Thairu was a Postdoctoral Research Fellow in Medicine at Stanford University in the Division of Infectious Diseases and, from 2010-2014 an Assistant Professor of Public Health at Touro University California and from 2014 an Assistant Consulting Professor at the Stanford University School of Medicine.

Infant Mortality in Tanzania

![]()

Every year, an estimated 3 million babies die before they reach 28 days of age. Africa has been described as ‘the most dangerous place for an infant to be born’ and it has one of the highest rates of newborn mortality worldwide.

In Tanzania in Africa, 22 out of 1000 babies will die before they are 28 days of age—this is more than 5 times the rate of newborn mortality in the United States which is estimated at 4 deaths out of 1000 live births.

Based on a research project in Pemba Island in Tanzania, in which I interviewed 38 mothers of newborns, I describe the behaviors that mothers undertook to protect their newborns from early death.

The results of the study showed that, overall, mothers perceive child birth as a dangerous event, however, they were reluctant to use hospital facilities for child birth as the hospitals were poorly equipped and understaffed. Mothers preferred to give birth at home with the help of traditional birth attendants, and the mothers perceived their newborns as particularly vulnerable from various forces including bad human intent and evil spirits. For this reason, caring for the newborn was both spiritual and biomedical. Spiritual forms of protection included burying the placenta after delivery, calling the baby to prayer within a few hours of delivery, and applying black soot to the newborn’s face to protect the baby from evil human intentions.

In addition, mothers engaged in biomedical behaviors such as immunizing their newborns and using clean delivery kits.

Overall, the results of this study indicate the fatalism and the lack of belief in biomedical ways of protecting newborns from illness and death in Pemba island. Perhaps this fatalism stems from the lack of public health facilities and hospitals in Pemba Island and in similar parts of sub-Saharan Africa.