Next time you go for a run, think about leaving your shoes at home.

Next time you go for a run, think about leaving your shoes at home.

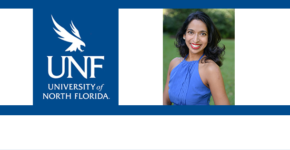

Tracy Alloway, professor of psychology at the University of North Florida, examines if running barefoot is better for your memory.

Dr. Tracy Alloway is a professor of psychology and the Graduate Program Director at the University of North Florida. She has spent over a decade being part of cutting-edge research on the importance of working memory in education and has led numerous government grants. In addition to publishing more than 100 scientific articles, she has also authored test batteries, published with Pearson, and seven books. He research has appeared in many media outlets, including Forbes, Good Morning America, the Today Show and the BBC.

Running Barefoot

Running barefoot is better than running with shoes for your working memory, according to our new study.

The experiment, designed by lead researcher Dr. Ross Alloway, and myself, is the first to show that running barefoot can lead to better cognitive performance than running with shoes.

Working Memory, our ability to recall and process information, is used throughout our lifespan. By improving it, we may be able to realize gains in key areas from school, to work, to retirement.

We enlisted 72 participants, aged between 18 and 44. Participants ran both barefoot and shod (wearing shoes) at a comfortable, self-selected pace, for approximately 16 minutes. Participants were monitored while they were on a running track while stepping on targets (poker chips on the ground) and when not stepping on targets. Working memory was measured before and after running.

There was a significant increase in working memory performance in the barefoot running condition, approximately 16 percent. There was no significant increase in working memory when running with shoes. The speed and heart rate of the participants was also measured, but neither was found to have any effect on working memory performance.

When running barefoot, one often has to avoid stepping on potentially hurtful objects by using precise foot placement. Thus, participants were required to step on flat objects to simulate running barefoot in an outdoors context. Though participants stepped on the flat objects when shod and barefoot, only the barefoot condition saw improvements in working memory, and only when they ran for 16 minutes.

It is possible that the barefoot condition required a more intensive use of working memory because of the extra tactile and proprioceptive demands associated with barefoot running, which may account for the working memory gains. But we need a combination of factors to see working memory improvements – running barefoot while focusing attention on the ground (as in the target condition), and running for over 15 minutes.