A small bird is pushing the limits of muscle performance.

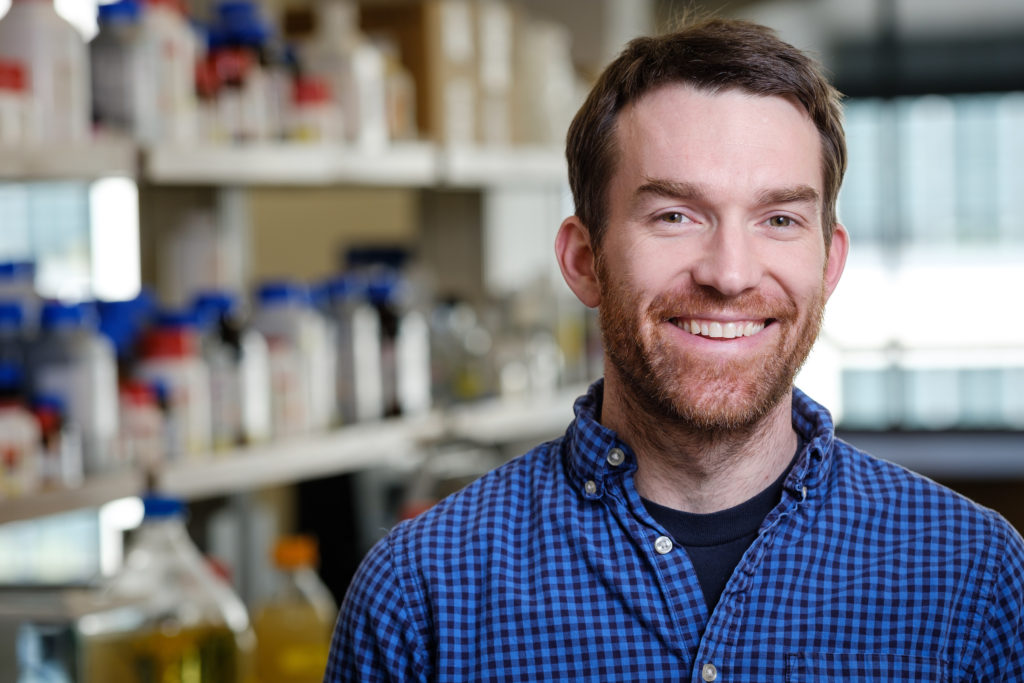

Matthew Fuxjager, assistant professor of biology at Wake Forest University, explores how one bird helps itself with faster muscle movements.

Dr. Matt Fuxjager is an Assistant Professor in the Biology Department at Wake Forest University. He received his MS from the University of North Carolina – Chapel Hill, studying magnetic orientation in hatchling loggerhead sea turtles. From there, Matt received his PhD from the University of Wisconsin – Madison, investigating how social interactions shape the ways in which animals behave in the future. Much of this work centered around Peromyscus mice, and how the androgenic hormones that are released in response to winning territorial intrusions act on the brain and body to enhance winning ability later in life. Matt completed a postdoctoral fellowship at the University of California – Los Angeles in both the Department of Integrative Biology & Physiology and the Laboratory of Neuroendocrinology, which is part of the UCLA Brain Research Institute. There, Matt studied how androgenic hormones interact with neuromuscular systems to help mediate the production of acrobatic social displays in tropical birds.

Roll Snap Golden Manakins

Golden-collared manakins are birds a little bigger than a cotton ball, but they have extraordinarily powerful wing muscles. For most bird species, the muscle connecting the shoulder-blade and forearm—the scapulohumeralis—isn’t noticeable. But in golden-collared manakins, the shoulder muscle is massive and contracts and relaxes 2 or 3-times faster than in other birds. Why? The answer comes down to courtship.

To find a mate, a male manakin has to dance with a number of acrobatic maneuvers. Our research team studies one of these movements, called the roll-snap. It’s produced by clapping the wings together at high speed— nearly 60 times per second, much faster than most bird muscles. The scapulohumeralis.is responsible for hitting the wings together.

But the golden-collared manakin is only one of four bearded manakin species, all of which use roll-snap displays. They evolved from one common ancestor in just 300,000 years—about the same amount of time that our own species has existed. We wondered if courtship helped the species diverge, because mating dances act like a secret code: if a male doesn’t produce the right moves, he won’t pass on his genes. The roll-snap display is the fastest move in the manakin’s repertoire, and female manakins are attracted to speed— so maybe differences in roll-snap speed help to keep the species from fusing back together?

To test this, we measured displays from all bearded manakins, finding that golden-collared manakins are faster than the other three. And it’s not just a matter of behavior— the golden-collared manakin also has a faster shoulder muscle than a slow-snapping relative. But then we found something surprising: even with all its speed, the superfast shoulder muscle eventually gets slower after every repeated contraction, as if it’s getting fatigued. Overcoming this boundary will require another innovation—thus pushing the limits of muscle performance once more.