What happened to fleeing slaves after they reached the end of the Underground Railroad?

What happened to fleeing slaves after they reached the end of the Underground Railroad?

Adam Arenson, associate professor of history and director of urban studies at Manhattan College, examines the lives of African-Americans in the North after escaping slavery.

Adam Arenson is an associate professor of history and the director of the urban studies program at Manhattan College. He is a historian of the cultural and political history of slavery, Civil War, and Reconstruction, as well as American cities throughout time, especially in the American West and on American borders. He is the author of the award-winning The Great Heart of the Republic: St. Louis and the Cultural Civil War (Harvard, 2011; paperback Missouri, 2015) and co-editor of Frontier Cities: Encounters at the Crossroads of Empire (Pennsylvania, 2013), and Civil War Wests: Testing the Limits of the United States (California, 2014), which was accompanied by a museum exhibition. He has also published a half-dozen articles, including pieces on Dred Scott’s family and Anglo-Saxonism in the Yukon Territory. See more about his varied projects, from the digital reconstruction of African North American communities to Los Angeles art and architecture, at http://adamarenson.com

After The Underground Railroad

What happened after the Underground Railroad?

We know the stories of fugitive slaves and their daring escapes north; we revel in the drama of these moments, when black and white Americans worked together, against the law, to do what was morally right.

Yet no one seems to think much about what happened next.

During the Civil War, at least 600 African North Americans returned to join the U.S. Army, and thousands more followed in the decades to come. Some went all the way south to Alabama, to reconnect with relatives; others found government jobs in Washington, D.C. Some trained as ministers in Ohio and New York; still others found jobs, later, in the automobile industry, growing up around Detroit. In 1870, Congress changed the U.S. Naturalization Act to include those “of African descent,” the first time non-whites were allowed to naturalize.

A few African North Americans were famous: Mifflin Gibbs became a judge, and an ambassador; the  political activist and newspaper editor Mary Ann Shadd Cary argued for woman’s suffrage and representation in Congress for D.C. residents.

political activist and newspaper editor Mary Ann Shadd Cary argued for woman’s suffrage and representation in Congress for D.C. residents.

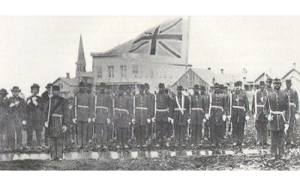

But many only left traces, in census records and family genealogies. Church records, fraternal group photographs, and school records reveal something of their accomplishments—and annual homecoming events, which continue among their descendants, celebrate their legacies.

I study African North Americans in order to emphasize the importance of the U.S.-Canada borderlands in the late nineteenth century, stretching our understanding of African American and Reconstruction history to embrace the whole continent, not just the former Confederacy. These men and women led the institutions that welcomed the Great Migration a few decades later.

Recovering the stories of these mostly unknown men and women provides a way to tell this wider history of the lives lived after the Underground Railroad.

Read More:

AdamArenson.com : Crossing the Border after the Underground Railroad