The opioid crisis has been reported, but maybe not to its full extent.

The opioid crisis has been reported, but maybe not to its full extent.

Donna Nelson, professor of chemistry at the University of Oklahoma, examines into the numbers.

Dr. Donna Nelson is a Professor of Chemistry at University of Oklahoma. Her research has always engaged the chemistry community and served professional societies and organizations, collectively described as work ensuring America’s Scientific Readiness. In her activities, she focuses on science education and impacting science by considering its communities. Her impact on the image of science and scientists includes being science advisor to television shows, such as the award-winning AMC production Breaking Bad, and holding offices, such as 2016 President of the American Chemical Society, the largest scientific society in the world.

The U.S. Fentanyl Challenge

Most people are generally aware of a fentanyl problem in the United States (US), but not necessarily of its magnitude. Quantifying a problem is often a good way to clarify it, so we collect and disseminate statistics about it as benchmarks in order to help track progress toward its mitigation.

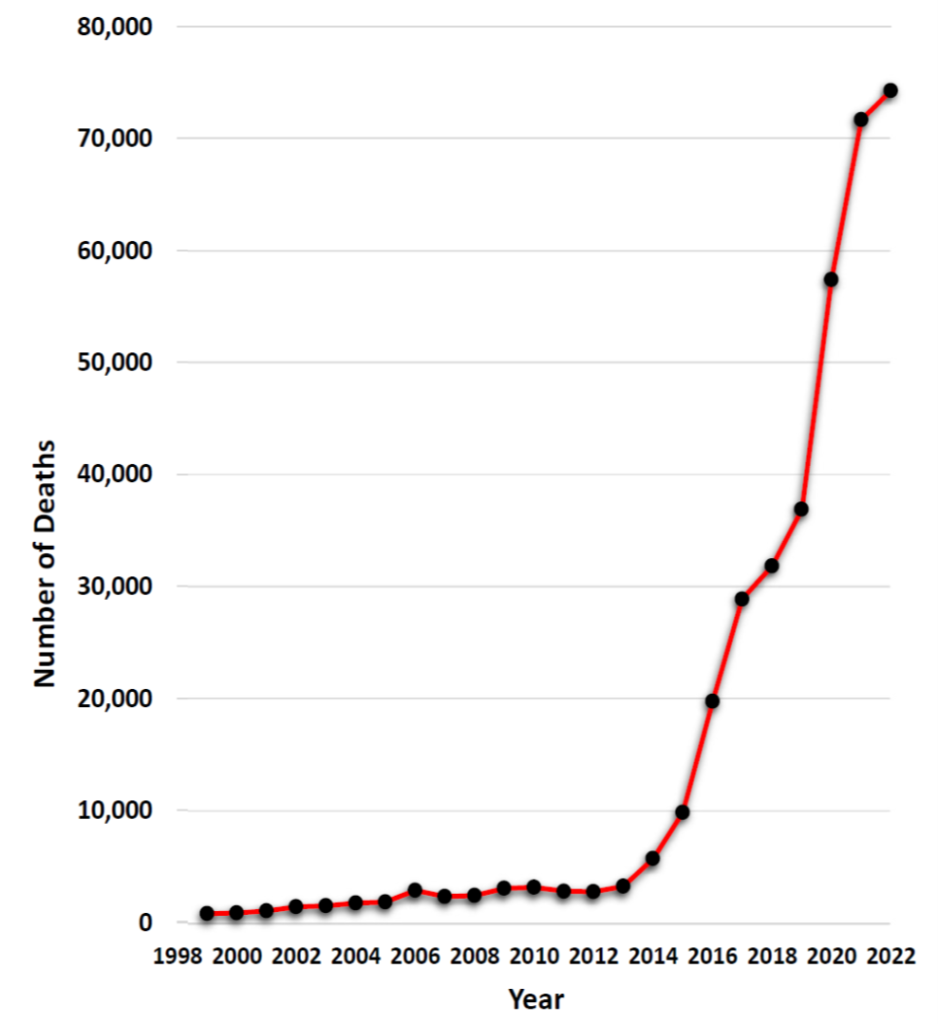

The number of deaths reported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) began increasing sharply in 2013 — from about 3,000 annual deaths to roughly 73,000 deaths in 2022. The rapid increase in only about 10 years was unexpected.

Deaths and death rates due to illicit fentanyl in the US continue to rise. A simple supply-and-demand relationship gives a rationale.

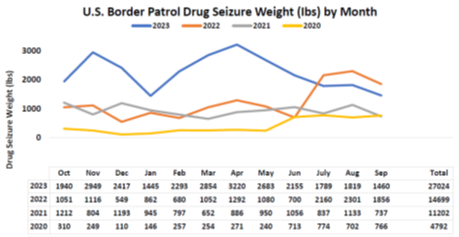

US Border Patrol seizures are also increasing annually. In 2023, over 27,000 pounds of illicit fentanyl were seized, which is enough to kill every person in the US more than 18 times.

Multiple factors have increased the supply of illicit fentanyl over time — border porosity, more aggressive smuggling operations by Mexico cartels, and unprecedented illicit exportation of fentanyl precursors to those cartels.

A deeper dive into CDC data reveals that the age groups most impacted by illicit fentanyl are those in their 20s and 30s, which include most college undergraduates. While teaching my organic chemistry classes at the University of Oklahoma, a few times each semester I spent a couple of minutes discussing fentanyl death rates. I advised students to “stay away from street drugs” because no one knows what’s in them.” I told the students, “It’s like playing Russian roulette.” Many students emailed me their thanks, sharing that they had lost a friend or family member to fentanyl. They said that my warning about fentanyl was the only one they had received and that we all should share this message.