Some of our possessions have more history than we realize.

Some of our possessions have more history than we realize.

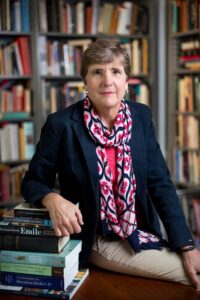

Suzanne Marchand, professor of history at Louisiana State University, looks into one such object.

Suzanne Marchand received her BA from UC Berkeley in 1984 and her PHD from the University of Chicago in 1992. She was assistant and associate professor at Princeton University between 1992 and 1999, at which time she moved to LSU, Baton Rouge, where she is now Boyd (University) Professor (LSU’s highest honor; she is only the 4th woman to be so honored). Her special field is European intellectual history since 1700. She is the author of two previous monographs, Down from Olympus: Archaeology and Philhellenism in Germany, 1750-1970 (Princeton UP, 1996) and German Orientalism in the Age of Empire: Religion, Race, and Scholarship (Cambridge UP, 2009), as well as the co-author of two textbooks and the author of many essays. She served as President of the German Studies Association between 2012 and 2014, and has been awarded several major fellowships. She has just published a book on the history of tableware: Porcelain: A History from the Heart of Europe (Princeton UP, 2020).

Porcelain

What can tableware tell you about European history?

Historians today are paying more attention than ever to the history of food and drink. This research brings us into conversation with natural scientists, museum professionals, and experts in business history and helps us answer questions such as: how did Europeans learn to love coffee, and why was my grandmother so attached to her Meissen sugar box?

Porcelain—the finest and most expensive grade of ceramics—has a particularly revealing story, especially for German historians. It was a Saxon would-be alchemist who in 1708 managed to replicate the Chinese recipe for white porcelain; but soon copycat factories began pumping out figurines and soup tureens, and later down-market teacups and men’s pipes. Decorations ran the gammut, from semi-clothed goddesses to monkeys playing bassoons, from military heroes to babies cuddling cats.

Luxuriously painted porcelains tell us much about what our richer ancestors found fascinating enough to buy and display. But the history of porcelain also tells us about its makers, marketers, and consumers: the entrepreneurs who lost their shirts when luxury markets cratered; the artisans who used kilns to toast chicory for their ersatz coffee. Luxury marketing virtually begins with Meissen porcelain, one of the first ‘brand names.’ But middle-class daughters, too, were taught to take pride in elegant holiday tables. So powerfully did porcelain signify ‘home’ that delicate pieces were carried across oceans by Jewish women fleeing the Nazis.

Porcelain’s Central European history may be at an end, as dozens of manufactories have recently closed. But many of us retain our own archives, in the form of our dusty, but still beloved, sugar boxes and holiday ‘china.’

Comments

One response to “Suzanne Marchand, Louisiana State University – Porcelain”

My son got me the book on porcelain as a gift. I read “Consider the fork” and “sapiens”. I enjoy learning about social history. For example, look at all the changes in our daily lives we have made just since the pandemic started.