Anne Frank has become the symbol of the Holocaust in The Netherlands, but there’s more to learn.

Anne Frank has become the symbol of the Holocaust in The Netherlands, but there’s more to learn.

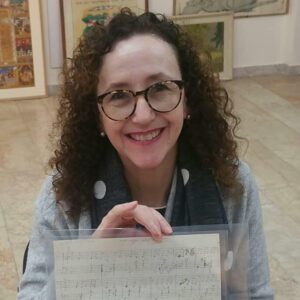

Naomi Yavneh Klos, professor of languages and cultures at Loyola University New Orleans, delves into more of this history.

Naomi Yavneh Klos, Ph.D. is a Fulbright Scholar at Windesheim Honours College in Zwolle, The Netherlands (Spring 2020), and Professor of Languages and Cultures at Loyola University New Orleans. The former Director of Loyola’s University Honors Program, where she led the creation of a curriculum emphasizing social justice and diversity learning outcomes, her research focuses on social justice pedagogy and the role of interfaith understanding as an essential component in diversity and community. Since 2018, she has taught in the International Summer Institute, “Tolerance, Diversity, and Lessons from the Holocaust,” jointly sponsored by Windesheim, Hanze Honours College, and Memorial Camp Westerbork. Her current project, “Imaginary Friends,” explores how our companions from history, texts, and traditions can help us engage with essential questions of empathy and compassion.

In Quarantine with Anne Frank

During this challenging moment of fear and social distancing, we keep hearing the name “Anne Frank.” On Facebook, a meme reminds us that “Anne Frank and seven other[s]…hid in a 450-square foot attic for 751 days.” Home-bound children are exhorted, “Be like Anne Frank” and keep a diary! Meanwhile, a journal admonishes, “Leave Anne Frank Alone.”

75 years after the end of World War II, the voice of Anne Frank, so poignantly preserved in her diary, is for many Americans the “single story” about the Holocaust and the Netherlands. Like all single stories, it is incomplete, a radical simplification of multiple narratives about Anne Frank, about the Dutch, and about the war.

Most Americans, for example, don’t know that the Netherlands lost a higher percentage of its Jewish population than did any other country in Western Europe. We hear nothing about the Dutch Hunger Winter of 1944-45, during which the Germans cut off almost all food and fuel supplies. Or that over 100,000 people, Jews and non-Jews alike, went into hiding; of the 25,000 of these onderduikers who were Jewish, 16,000 or more survived. We do not know that Anne Frank was not a Dutch citizen but an immigrant from Germany; what we know as her “diary” is in fact a composite of Anne’s original diary, and her own revision of that diary, which she dreamed of publishing after the war under the title, Het achterhuis, the Secret annex.

The diary is not the whole story, but its power is undeniable.