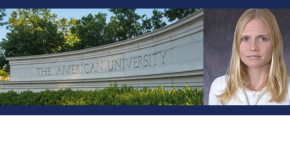

Krista_Tuomi, SIS, faculty

On American University Week: Need money for a project? Ask the crowd.

Krista Tuomi, assistant professor at the school of international service at American University, discusses the pitfalls of relying on crowdfunding for cash.

Krista Tuomi is a professor in the International Economic Policy program at the School of International Service, American University. After teaching for many years in her home country, South Africa, she is enjoying the highs and lows of teaching economics and politics in DC. Currently she “imparts wisdom” to students on topics such as economic policy, crowdfunding, entrepreneurship, investment, and financial policy. She has worked for many years as a policy analyst in the areas of innovation and investment. Recently her focus has been on best practice in the start-up investment climate, particularly on policy related to angel investing, crowdfunding and seed financing. She also conducts workshops on all forms of financing, both for small business and non-profits. In particular, she is regular workshop presenter for SCORE, the Small Business Administration’s volunteer branch. Her passion for the field of innovation and entrepreneurship extends into her other pro-bono work as well. Apart from working with SCORE, she is involved with the Angel Capital Association, the Veteran’s Small Business Challenge Competition, and Syracuse’s Institute for Veterans and Military Families. She also publishes widely in the field of innovation financing, with recent papers and blogs focusing on the costs of software development, and best practice in entrepreneur eco-systems.

Crowdfunding

There are quite a few misperceptions about crowdfunding, but one ranks above all — the belief that it’s a quick and easy way to raise large sums of money for just about any idea, start-up, project, or cause. News reports about crowdfunding repeatedly make it sound simpler and more lucrative than it is.

Equity crowdfunding, in which entrepreneurs seek financing from multiple sources in exchange for shares in a company, may be of benefit to certain types of start-ups, such as a small lifestyle firm with no sensitive intellectual property and no need for much follow-on funding. Nevertheless, I tend to guide start-ups to the other forms of crowdfunding (reward based and pre-sale), and to see it as less of a way to raise funds, and more of way to build a community, conduct beta testing or perform market research. Even then (and this also applies to those who hope to raise money for projects), potential crowdfunders should be aware of its difficulty and cost. These include reputation effects if campaign goals are not met; platform fees; and time spent “working the crowd”.

The time factor, in particular, can be overwhelming to novices. Most successful start-ups have several hundred backers on board before the online funding campaign even starts, plus an extensive social media plan, a catchy video viewable on any size screen, and people who are ready to answer questions and drum up publicity during the entire length of the campaign. Many crowdfunding neophytes don’t realize that outside of their own inner circle, only 3 to 5 percent of outside viewers buy in.

With a well prepared plan and realistic expectations, crowdfunding can be a useful tool. But today, however, it is not the financial panacea that many believe it to be.