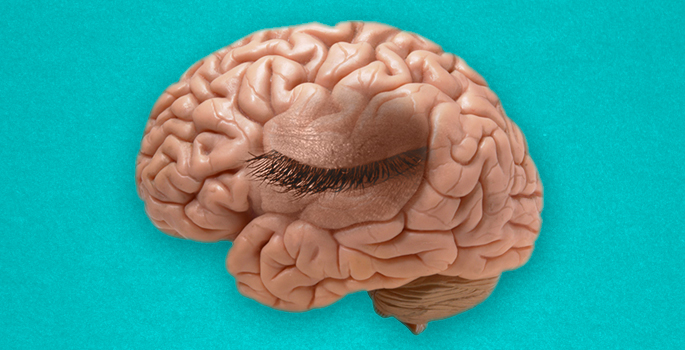

Does your mind’s eye blink?

Alex Maier, assistant professor of psychology at Vanderbilt University, discusses this question.

Alex Maier obtained his Ph.D. in neuroscience at the Max Planck Institute of Cybernetics in Germany. He worked as a research fellow at the U.S. National Institutes of Health before joining Vanderbilt’s faculty as an assistant professor, where he teaches in the Department of Psychology in the College of Arts and Science. Maier x has received awards from the Society for Neuroscience, the National Institutes of Mental Health, the Whitehall Foundation, the Minds Science Foundation as well as the Knights Templar Eye Foundation. He has been elected as a Fellow of the Sloan Foundation and a Kavli Fellow of the National Academy of Sciences. His current research on the neurobiological basis of vision is funded by the National Institutes of Health.

Mind’s Eye Blink

As humans, we have a remarkable and fairly unique ability to look in one direction while paying attention to another. Paying attention to a particular location improves our ability to see things at that location, even if our eyes are pointed elsewhere. Our eyes and our attention constantly move around the world, just not always together.

The visual cortex processes both information from our eyes and feedback from the rest of the brain to help us understand what we are seeing, including information guiding our attention. Once a person pays attention to a certain location, brain activity corresponding to that location increases. We wanted to know what happens before attention settles, while a person moves attention between locations.

We had subjects play a simple video game that required them to keep their eyes fixed while moving their attention. Once the subjects learned to play the game well—it is surprisingly hard to keep your eyes still—we measured visual cortex activity while they played.

We found that as attention moves from one location to another, overall activity in the visual cortex briefly decreased. By simultaneously tracking many neurons and applying sophisticated computational analyses, we traced the source of this disruption to parts of the brain guiding attention, not to the eyes. This is similar to what happens while our eyes are moving. During eye movement, activity in the visual cortex temporarily decreases to avoid the disorienting experience of seeing the rapid movement of the image.

There seems to be a real biological basis for the proverbial “cost” for paying attention, or more precisely, for changing attentional focus. This cost takes the form of brief moments of reduced brain responses to sensory stimuli while we are shifting our attention. The brain thus seems to internally “blink” for a moment, not processing the visual world as well as normal. Previous studies have found behavioral evidence that this is the case, but our study points towards the brain mechanism underlying this phenomenon.

Comments

One response to “Alex Maier, Vanderbilt University – Mind’s Eye Blink”