Could a cooldown be coming to Europe?

Could a cooldown be coming to Europe?

Jaime Palter, assistant professor of oceanography at the University of Rhode Island, determines whether global warming is slowing the ocean currents that bring heat to the continent.

Palter joined the University of Rhode Island’s Graduate School of Oceanography in September, 2015. She studies large-scale ocean circulation and its interactions with climate and the living ocean using both observational and modeling techniques. In collaboration with her students and colleagues, Palter has addressed issues such as the influence of the ocean circulation on the supply of nutrients to marine phytoplankton, the variability of North Atlantic currents at a kilometer beneath the ocean’s surface, and the response of deep ocean convection to global warming. She is a Massachusetts native who got her doctorate at Duke University.

The Great Ocean Conveyor and Europe’s Winters

European climate variability over decades and longer is strongly influenced by temperature swings of its neighboring ocean, the North Atlantic. However this influence can only be detected in the spring, summer and fall. In wintertime, the North Atlantic imprint is missing. This absence is puzzling in light of the fact that Europe’s mild winters are a consequence of its enviable location downwind of the North Atlantic.

Recently, my student, Ayako Yamamoto, and I identified a cause of the missing North Atlantic influence on European winters. And the answer lies in the winds themselves.

In decades in which North Atlantic sea surface temperatures are elevated, winds take a more northern route to Europe. In contrast, in decades of coolest sea surface temperature, swifter winds extract more heat from the western and central Atlantic before arriving in Europe.

In this way, the distinct atmospheric pathways hide the ocean temperature swings from Europe in winter.

What remains controversial is whether the atmosphere is the tail to the ocean’s dog or vice versa. In other words, is the ocean circulation setting the slow temperature fluctuations at its surface and driving the wind variability, or is the atmosphere is the more important agent?

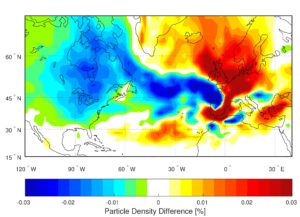

Many climate models suggest the ocean is an important driver. If these models are correct, then our research has implications for the future of European climate. A system of ocean currents, popularly referred to as the “Great Ocean Conveyor,” bring warm waters to the North Atlantic. This current system is predicted to slow in response to global warming. Its slowdown would cool the North Atlantic, much as it cooled in the 1970-80s.

It is often presumed that the cooler North Atlantic will quickly lead to cooling in Europe, or at least a slowdown in its rate of warming. But our research suggests that the atmosphere might stop this relative cooling from showing up in Europe in winter in the decades following a slowdown of the Great Ocean Conveyor.