You may know your morning routine like the back of your hand, but some people struggle with ordinary tasks.

You may know your morning routine like the back of your hand, but some people struggle with ordinary tasks.

David Badre, associate professor in the department of cognitive, linguistic and psychological sciences at Brown University, determines that examining how the brain puts tasks in the right order can help people who have difficulty with day to day routines.

David Badre received his B.S. from the University of Michigan in 2000, and his Ph.D. from the Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences at MIT in 2005. Following a postdoctoral fellowship at the University of California, Berkeley, he joined Brown’s Department of Cognitive, Linguistic, and Psychological Sciences as Assistant Professor in 2008 and was promoted to Associate Professor in 2014. He is also an affiliate of the Brown Institute for Brain Science and a trainer in the Neuroscience Graduate Program. His lab at Brown focuses on the cognitive neuroscience of memory and cognitive control with an emphasis on frontal lobe function and organization. Dr. Badre serves on the editorial boards of Psychological Science, Cognitive Science, and Behavioral Neuroscience, and he is Section Editor covering “Executive Function and Cognitive Control” for Neuropsychologia. His research is supported by NINDS and NIMH at the NIH and has been recognized by early career awards, including an Alfred P. Sloan Foundation Fellowship in Neuroscience, a James S. McDonnell Scholar Award in Understanding Human Cognition, and the Cognitive Neuroscience Society Young Investigator Award.

Executive Functions

Everyday tasks commonly involve carrying out a sequence of smaller tasks en route to a larger goal. For example, making coffee often entails scooping grinds or adding water to a drip machine. Our ability to get the right little tasks together and in the right order requires a capacity known as executive function. Executive functions are particularly vulnerable to brain disease and disorder and so a wide range of neurological and psychiatric problems feature executive deficits. Patients commonly have difficulty carrying out even routine sequential tasks, which is a major obstacle to independent living. But, we haven’t understood how the brain normally carries out complex sequential behaviors.

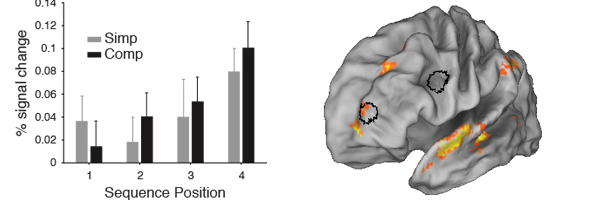

To address this question, a postdoctoral fellow in my lab, Theresa Desrochers, tested healthy human volunteers while they performed a sequence of simple tasks on a computer. Importantly, there were no cues available to them that told them what task to do next. They had to keep track of where they were and had to choose the right task to perform at the right moment. Using functional MRI, we found that activity in a specific network of brain areas tracked progress through a sequence. This network included the very front-most part of the frontal lobes: the rostrolateral prefrontal cortex. We then used a procedure, called transcranial magnetic stimulation, to safely stimulate this region at different points in the sequence. We found that we could induce more errors by stimulating this region toward the end rather than the beginning of a sequence. These results indicate that the brain’s executive systems are not necessary throughout a sequence. Rather, there are moments – important points in the sequence – where the executive keeps us on track. Insights from this study help us better understand how the executive works and could lead to future applications to aid executive function in real life.

Read More:

The Badre Lab

Follow the lab on Twitter!