How does your sense of smell affect your behavior?

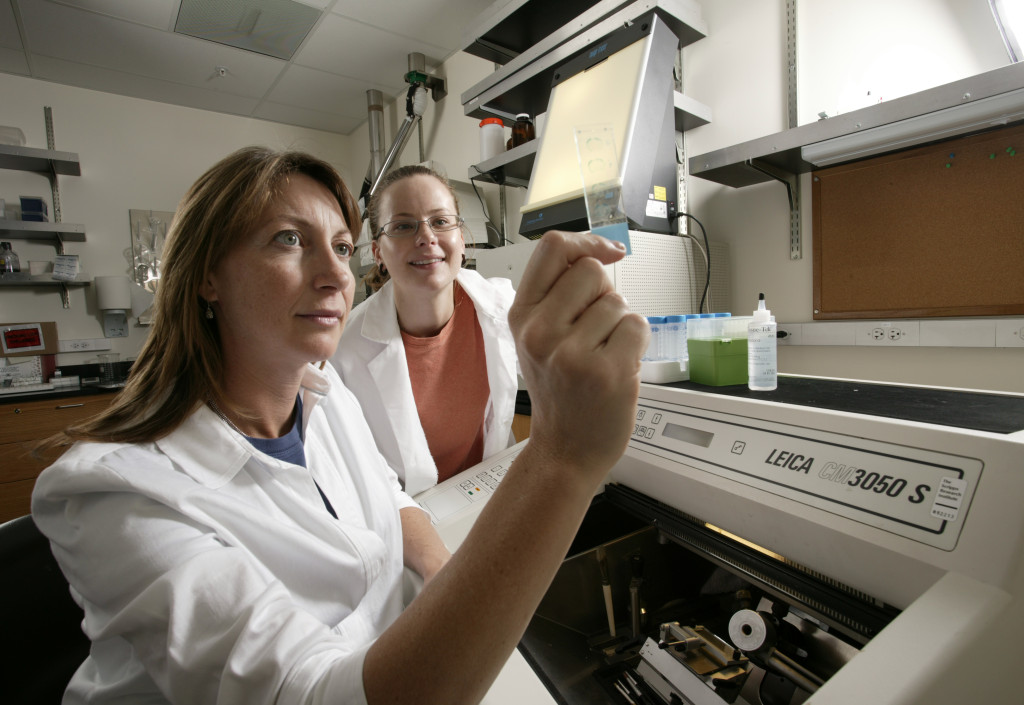

Lisa Stowers, associate professor at the Scripps Research Institute, explains that we’re learning how your brain might not have a say in the matter.

Lisa Stowers received her PhD in Molecular & Cellular Biology from Harvard University in 1997, where she used a molecular genetic approach to study the neurobiology of mouse behavior. Since then, her research has focused on how neurons detect and respond to pheromones. Today she serves as associate professor in the Department of Molecular and Cellular Neuroscience at The Scripps Research Institute (TSRI). Her research has shown how pheromones and other chemical cues in mice influence male-male aggression, pup-suckling, inter-species fear, female reproductive behavior, and scent marking.

Smell & Behavior

My lab studies how the sense of smell affects behavior.

For years, we’ve understood sensory detection as a division of labor….the sensory neuron’s job is to detect available stimuli from the surroundings and the brain’s job is to figure out how to respond.

Of all the stimuli that our sensory neurons detect, only a small fraction is important to our brain. For example, our brain chooses to ignore most of the stimuli detected at a noisy party in order to focus on a single conversation. However, if someone across the room utters your name, you immediately hear it. That proves that the sensory system is doing its job of gathering all available stimuli.

But a recent discovery in my lab shows that the sense of smell does not always obey this rule. We had been investigating how the brain chooses to make male pheromones attractive to a female mouse when she is fertile, yet males have no appeal when she is not.

To our surprise, the brain has no say in this matter. We found that the female mouse’s lack of sexual attraction is because cycling female hormones shut off male-detecting sensory neurons—completely preventing the information from traveling to the brain. Interestingly, other sensory neurons, such as those that detect predators, continue to pass all detected cues to the brain irrespective of her hormone state.

The female mouse is actually ignoring the male mouse because she can’t sense he is present.

We are now investigating whether hunger hormones similarly regulate the detection of food odors.

Read More:

To Mark Territory or Not to Mark Territory: Breaking the Pheromone Code

![Camera: DCS330C Serial #: K330C-2297 Width: 1504 Height: 2008 Date: 12/18/97 Time: 9:40:35 DCS3xx Image FW Ver: 3.2.3 TIFF Image Look: Product Sharpening Requested: Yes Tagged Counter: [7028] ISO Speed: 125 Aperture: f11 Shutter: 1/125 Max Aperture: f4 Min Aperture: f33.9 Exposure Mode: Manual (M) Compensation: +0.0 Flash Compensation: +0.0 Meter Mode: Matrix Flash: None Drive Mode: Single Focus Mode: AF-S/Wide Self-timer: No Focal Length (mm): 79.4 Lens Type: Gen 1 D-Type AF Nikkor White balance: Preset (Daylight) Time: 09:40:35.848](https://academicminute.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/stowers_lisa-221x300.jpg)

Comments

One response to “Lisa Stowers, Scripps Research Institute – Smell & Behavior”