There is still so much mystery out in deep space.

There is still so much mystery out in deep space.

But, with amazing research from folks like Eddie Baron, we’re continually learning more about the universe we inhabit. Today on The Academic Minute, a nuclear physicist from the University of Oklahoma explains type Ia supernovae.

Eddie Baron received his PhD in Nuclear Physics from Stony Brook University. He was a research associate at Steward Observatory and then a research associate at Stony Brook University. He has been on the faculty at the University of Oklahoma since 1990, where he is George Lynn Cross Research Professor of Physics & Astronomy.

Type Ia Supernovae

Type Ia supernovae are great cosmic probes because their brightness is almost always the same and can be standardized empirically.

Type Ia supernovae are great cosmic probes because their brightness is almost always the same and can be standardized empirically.

These objects were used to discover the Dark Energy in 1999 and this accomplishment was recognized with the Nobel Prize in 2011.

However, the nature of the stars that blow up remain a bit of a mystery.

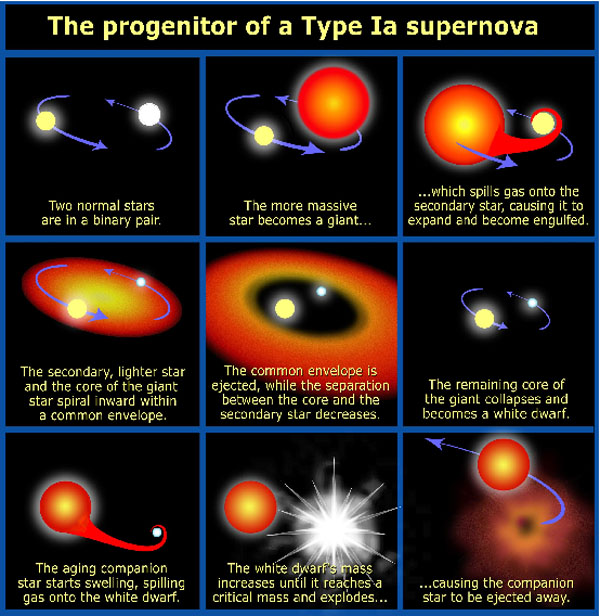

In order to understand the near uniform brightness the classic paradigm of a Type Ia explosion involves a carbon/oxygen white dwarf reaching the Chandrasekhar mass. The Chandrasekhar mass is a unique mass of just less than 1.4 time the mass of the sun. The mass of the white dwarf is increased by accreting material from a companion. That is, the white dwarf is in a binary star system, with two stars orbiting around a common center of mass.

As we discover more and more of these transient objects, we find that there are indeed variations in the nature of the explosion.

Observations and models of the variations have cast doubt upon the validity of the classic model, despite the appeal that it leads to a standard system.

Many in the supernova community believe that a natural explanation for these variations is to throw out the Chandrasekhar mass model, with its unique standard mass and invoke the merger of two white dwarfs, whose mass could vary substantially from system to system.

My group is not ready to abandon the Chandrasekhar model and is trying to show that it still could be valid in many (but maybe not all) explosions.

This is a fascinating example of the scientific enterprise; different groups support different models for quite human reasons, including pure creativity and ambition.

Nevertheless, the scientific method will eventually lead to a general consensus. Stephen Jay Gould explained well how science is a human endeavor, “cultural embeddness” which nevertheless seeks and leads toward the truth.