Ski resorts aren’t the only ones that depend on a good base of snow in the winter.

Ski resorts aren’t the only ones that depend on a good base of snow in the winter.

Justin Mankin, a postdoctoral fellow at Columbia University, describes how a changing climate may change the way cultures get their water in the spring and summer.

Mankin is a climate scientist jointly appointed at Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory and NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies under the Earth Institute. His research aims to advance understanding and responses to global warming’s impacts on people. He focuses on two of the major sources of uncertainty in climate impacts assessments: the chaos innate to the climate system and the complexity of how people respond to climate stress. His hope is that his research can help inform the adaptation and risk management decisions that people undertake in response to the uncertain threats from climate change. Prior to earning his PhD from Stanford University, he served as an intelligence officer. He also holds degrees from Columbia University (BA, MPA) and the London School of Economics (MSc).

Declining Snowpacks

The anthropologist Franz Boas claimed that the Inuit had over 50 words for snow. They don’t, but his larger point—that social practices should be understood in the context of their cultures—stands. Snow was so significant that the Inuit parsed its varied forms and functions into many words.

Snow’s significance is not only cultural: Every winter, snow advances from the poles to the mid-latitudes, reflecting sunlight and influencing the weather patterns people and ecosystems expect. Snow cover insulates trees’ roots from cold winter air while ensuring pests don’t survive the winter.

Snowpack also serves as its own storage reservoir, regulating water runoff, pulsing water and nutrients to people and ecosystems downstream precisely when their spring and summer water demands increase.

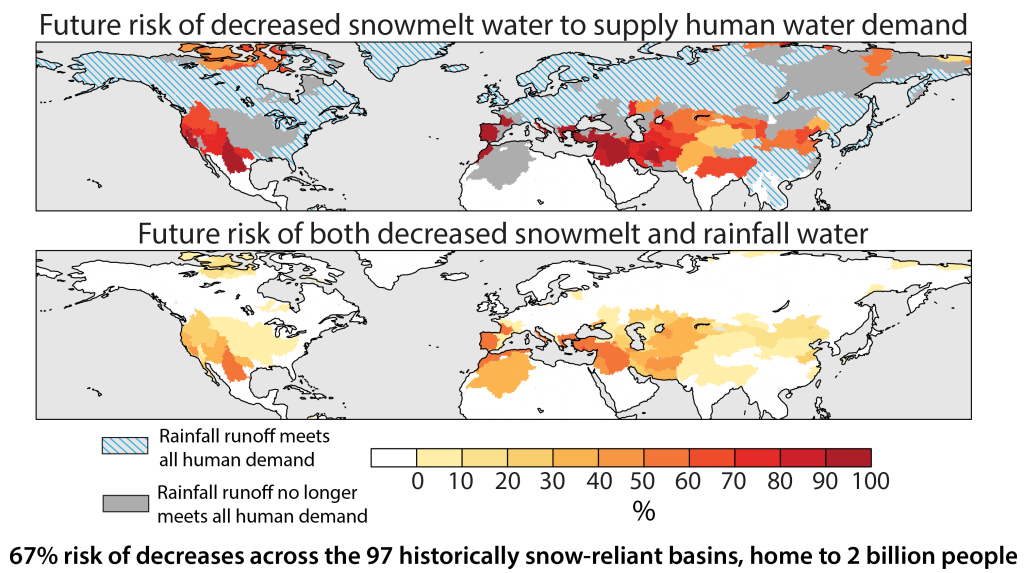

My colleagues and I identified where people uniquely depend on seasonal snowmelt to help identify where future snow changes represent the most pressing adaptation challenges. We find that a quarter of river basins in the Northern Hemisphere, home to about 2 billion people, are dependent on water stored in snowpack. For these basins, snow is indelibly tied to people’s practices of water use, as it is for the Inuit.

In a warmer world, we expect less snow to accumulate. And the snow that does accumulate, we expect to runoff earlier in the year. But, a warmer atmosphere will also hold more moisture, potentially bringing greater rains to quench water demands, and if the temperature remains low enough, more snow. This mix of temperature and precipitation variations, plus global warming, complicates our experience of snow changes.

Despite these uncertainties, we find that the future climate’s potential to supply present day water demand will decrease for many places, including basins of the American West, the Anatolian, Iberian, and Aegean peninsulas, and the Middle East. These risks are large and a rightful cause for discussion about how best to respond, because water demands will likely increase along with populations. For the Inuit and many other cultures, snow will remain important, but our practice of reliance on it as a seasonal source of water will change.